Crash de 1929

O Crash de 1929 foi um dos crashes bolsistas mais devastadores da história Americana. Ele consiste da Quinta-Feira negra (24 de Outubro de 1929), o crash inicial, e a Terça-Feira negra (29 de Outubro de 1929), o crash que semeou o pânico geral, 5 dias mais tarde. <ref>[1] "As cotações chegaram ao que aparenta ser um patamar permanentemente elevado. A euforia a os ganhos financeiros desse grande bull market foram estrelhaçados a 24 de Outubro de 1929, a Quinta-Feira negra, quando as cotações na NYSE colapsaram. As cotações cairam nesse dia e continuaram a cair, a uma velocidade sem precedentes, durante um mês inteiro."</ref>

Nos dias que precederam a Quinta-Feira negra o mercado estava instável. Períodos de venda em pânico e volumes elevados de transacções eram intervalados com breves períodos de subida de cotações e recuperação. Após o crash o Dow Jones recuperou no início de 1930, apenas para novamente cair, chegando ao fundo do grande bear market em 1932. O mercado não voltou aos seus níveis pre-1929 até ao final de 1954 <ref name="yahoo">DJIA 1929 to Present (Yahoo! Finance).</ref> e atingiu no seu ponto mais baixo, em 8 de Julho de 1932 , níveis que só tinham sido atingidos nos anos 1800s. <ref name="LiquidMarkets">Dow Jones 1900-2000</ref>

| “ | Quem tivesse comprado acções no meio de 1929 e as tivesse mantido, teria passado a maior parte da sua vida adulta antes de voltar ao breakeven. | ” |

Índice

Timeline

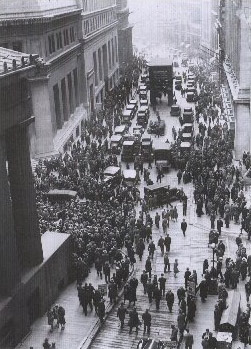

Após um supreendente bull market de 5 anos que viu o Dow Jones quintuplicar, as cotações atingiram o seu pico nos 381.17 em 3 de Setembro de 1929. Depois, o mercado caiu acentuadamente durante um mês, perdendo 17% do seu valor nesta primeira queda. As cotações encetaram aí uma recuperação de mais de metade das perdas em uma semana, apenas para voltarem a cair imediatamente após essa recuperação. A queda então acelerou para dentro da chamada "Quinta-Feira negra" (24 de Outubro de 1929). Um número recorde 12.9 milhões de acções foi transaccionado nesse dia.

Às 13:00 de Sexta-feira, 25 de Outubro, alguns dos banqueiros líderes de Wall Street reuniram-se para procurar uma solução para o pânico e caos no trading floor. Esta reunião incluía Thomas W. Lamont, CEO do Morgan Bank; Albert Wiggin, CEO do Chase National Bank; e Charles E. Mitchell, presidente do National City Bank. Eles escolheram Richard Whitney, vice-presidente da bolsa, para os representar. Com os recursos financeiros dos banqueiros a suporta-lo, Whitney colocou um bid para comprar um grande bloco de acções da US Steel a um preço bem acima do preço presente do mercado. À medida que os traders surpreendidos olhavam, Whitney colocou depois bids similares em outras blue chips. Esta táctica era similar a uma táctica que foi usada para terminar o pânico de 1907, e teve sucesso em estancar a queda nesse dia. Neste caso, porém, o descanso seria apenas temporário.

Durante o fim de semana, os acontecimentos foram dramatizados pelos jornais Americanos. Na Segunda-Feira, 28 de Outubro, mais investidores decidiram sair do mercado, e a queda continuou com uma perda recorde de 13% no Dow Jones nesse dia. No dia seguinda, a Terça-Feira negra, 29 de Outubro, 16.4 milhões de acções foram transaccionadas, o que bateu o recorde estabelecido 5 dias antes e não foi excedido até 1969. O autor Richard M. Salsman escreveu que em 29 de Outubro - entre rumores de que o Presidente Americano Herbert Hoover não vetaria o acto tarifário Smoot-Hawley as cotações cairam ainda mais."<ref name="salsman" /> William C. Durant juntou-se com membros da família Rockfeller e outros gigantes financeiros para comprar grandes quantidades de acções de forma a demonstrar ao público a sua confiança no mercado., mas os seus esforços falharam em parar a queda. O Dow Jones perdeu outros 12% nesse dia. O ticker não parrou de correr até cerca de 19:45 dessa tarde. O mercado perdeu $14 biliões em valor nesse dia, totalizando uma perda nessa semana de $30 biliões, 10 vezes mais que o orçamento do governo federal, e bastante mais do que o governo dos EUA tinha gasto em toda a 1ª Guerra Mundial.<ref>pbs.org – New York: A Documentary Film</ref>

Um fundo intermédio ocorreu em 13 de Novembro, com o Dow a fechar a 198.6 nesse dia. A partir desse ponto, o mercado recuperou durante vários meses, com o Dow a atingir um pico secundário nos 294.0 em Abril de 1930. O mercado entraria novamente numa queda estável em Abril de 1931 que não terminaria até 1932, quando o Dow fechou a 41.22 no dia 8 de Julho, concluindo uma queda de 89% desde o seu topo. Este foi o ponto mais baixo a que o mercado esteve desde o século XIX.<ref name = "Liquid Markets">Liquid Markets.</ref>

Salsman comentou que "Em Abril de 1942, as cotações das acções Americanas ainda estavam 75% abaixo do seu pico de 1929 e não voltariam a esse nível até Novembro de 1954 - quase um quarto de século mais tarde."<ref name="salsman" />

Fundamentais económicos

Dow Jones Industrial, 1928-1930 The crash followed a speculative boom that had taken hold in the late 1920s, which had led millions of Americans to invest heavily in the stock market, a significant number even borrowing money to buy more stock. By August 1929, brokers were routinely lending small investors more than 2/3 of the face value of the stocks they were buying. Over $8.5 billion was out on loan, more than the entire amount of currency circulating in the U.S.<ref>pbs.org — New York: A Documentary Film</ref> The rising share prices encouraged more people to invest; people hoped the share prices would rise further. Speculation thus fueled further rises and created an economic bubble. The average P/E (price to earnings) ratio of S&P Composite stocks was 32.6 in September 1929 <ref> Shiller, Robert (2005-03-17). "Irrational Exuberance, Second Edition". Princeton University Press. Consultado a 2007-02-03.</ref>, clearly above historical norms.

On October 24, 1929 (with the Dow just past its September 3 peak of 381.17), the market finally turned down, and panic selling started. 12,894,650 shares were traded in a single day as people desperately tried to mitigate the situation. This mass sale was considered a major contributing factor to the Great Depression. Economists and historians, however, frequently differ in their views of the Crash's significance in this respect. Some hold that political over-reactions to the crash, such as the passage of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act through the U.S. Congress, caused more harm than the Crash itself.

Official investigation of the Crash

In 1931, the Pecora Commission was established by the U.S. Senate to study the causes of the Crash. The U.S. Congress passed the Glass-Steagall Act in 1933, which mandated a separation between commercial banks, which take deposits and extend loans, and investment banks, which underwrite, issue, and distribute stocks, bonds, and other securities.

After the experience of the 1929 crash, stock markets around the world instituted measures to temporarily suspend trading in the event of rapid declines, claiming that they would prevent such panic sales. The one-day crash of Monday, October 19, 1987, however, was even more severe than the Crash of 1929. On so-called Black Monday of 1987, the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell a full 22.6% (the markets quickly recovered, posting the largest one-day increase since 1932 only two days later).

Impact and academic debate

The Wall Street Crash had a major impact on the U.S. and world economy, and it has been the source of intense academic debate—historical, economic and political—from its aftermath until the present day. The crash marked the beginning of widespread and long-lasting consequences for the United States. The main question is: Did the crash cause the depression, or did it merely coincide with the bursting of a credit-inspired economic bubble? The decline in stock prices caused bankruptcies and severe macroeconomic difficulties including business closures, firing of workers and other economic repression measures. The resultant rise of mass unemployment and the depression is seen as a direct result of the crash, though it is by no means the sole event that contributed to the depression; it is usually seen as having the greatest impact on the events that followed. Therefore the Wall Street Crash is widely regarded as signaling the downward economic slide that initiated the Great Depression.

Many academics see the Wall Street Crash of 1929 as part of an historical process that was a part of the new theories of Boom and bust. According to economists such as Joseph Schumpeter and Nikolai Kondratieff the crash was merely a historical event in the continuing process known as Economic cycles. The impact of the crash was merely to increase the speed at which the cycle proceeded to its next level. According to the economist Milton Friedman, in the immediate aftermath of the crash, the Federal Reserve did not sufficiently expand the money supply and so turned the recession into a depression.

Ver também

Referências

Bibliografia

- Brooks, John. (1969). Once in Golconda. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-393-01375-8.

- Galbraith, John Kenneth. (1955). The Great Crash: 1929. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-85999-9.

- Klingaman, William K. (1989). 1929: The Year of the Great Crash. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-060-16081-0.

- Salsman, Richard M. “The Cause and Consequences of the Great Depression” in The Intellectual Activist, ISSN 0730-2355.

- “Part 1: What Made the Roaring ’20s Roar”, June, 2004, pp. 16–24.

- “Part 2: Hoover’s Progressive Assault on Business”, July, 2004, pp. 10–20.

- “Part 3: Roosevelt's Raw Deal”, August, 2004, pp. 9–20.

- “Part 4: Freedom and Prosperity”, January, 2005, pp. 14–23.

- Shachtman, Tom. (1979). The Day America Crashed. New York: G.P. Putnam. ISBN 0-399-11613-3.