Diferenças entre edições de "Crash de 1929"

| Linha 15: | Linha 15: | ||

Após um supreendente bull market de 5 anos que viu o Dow Jones quintuplicar, as cotações atingiram o seu pico nos 381.17 em 3 de Setembro de 1929. Depois, o mercado caiu acentuadamente durante um mês, perdendo 17% do seu valor nesta primeira queda. As cotações encetaram aí uma recuperação de mais de metade das perdas em uma semana, apenas para voltarem a cair imediatamente após essa recuperação. A queda então acelerou para dentro da chamada "Quinta-Feira negra" (24 de Outubro de 1929). Um número recorde 12.9 milhões de acções foi transaccionado nesse dia. | Após um supreendente bull market de 5 anos que viu o Dow Jones quintuplicar, as cotações atingiram o seu pico nos 381.17 em 3 de Setembro de 1929. Depois, o mercado caiu acentuadamente durante um mês, perdendo 17% do seu valor nesta primeira queda. As cotações encetaram aí uma recuperação de mais de metade das perdas em uma semana, apenas para voltarem a cair imediatamente após essa recuperação. A queda então acelerou para dentro da chamada "Quinta-Feira negra" (24 de Outubro de 1929). Um número recorde 12.9 milhões de acções foi transaccionado nesse dia. | ||

| − | + | À 1:00 da tarde de Sexta-feira, 25 de Outubro, alguns dos banqueiros líderes de Wall Street reuniram-se para procurar uma solução para o pânico e caos no trading floor. Esta reunião incluía [[Thomas W. Lamont]], CEO do [[JPMorgan Chase|Morgan Bank]]; [[Albert Wiggin]], CEO do [[Chase Manhattan Bank|Chase National Bank]]; e [[Charles E. Mitchell]], presidente do [[Citibank|National City Bank]]. Eles escolheram [[Richard Whitney]], vice-presidente da bolsa, para os representar. Com os recursos financeiros dos banqueiros a suporta-lo, Whitney colocou um [[Bid|bid]] para comprar um grande bloco de acções da US Steel a um preço bem acima do preço presente do mercado. À medida que os traders surpreendidos olhavam, Whitney colocou depois bids similares em outras [[Blue chip|blue chips]]. Esta táctica era similar a uma táctica que foi usada para terminar o [[Pânico de 1907|pânico de 1907]], e teve sucesso em estancar a queda nesse dia. Neste caso, porém, o descanso seria apenas temporário. | |

| + | |||

Over the weekend, the events were dramatized by the newspapers across the United States. On Monday, [[October 28]], more investors decided to get out of the market, and the slide continued with a record 13% loss in the Dow for the day. The next day, "Black Tuesday", [[October 29]] [[1929]], and 16.4 million shares were traded, a number that broke the record set five days earlier and that was not exceeded until [[1969]]. Author [[Richard Salsman|Richard M. Salsman]] wrote that on [[October 29]]—amid rumors that [[U.S. President]] [[Herbert Hoover]] would not veto the pending [[Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act|Smoot-Hawley Tariff]] bill—stock prices crashed even further."<ref name="salsman" /> [[William C. Durant]] joined with members of the [[Rockefeller family]] and other financial giants to buy large quantities of stocks in order to demonstrate to the public their confidence in the market, but their efforts failed to stop the slide. The DJIA lost another 12% that day. The ticker did not stop running until about 7:45 that evening. The market lost $14 billion in value that day, bringing the loss for the week to $30 billion, ten times more than the annual budget of the federal government, far more than the U.S. had spent in all of [[World War I]].<ref>[http://www.pbs.org/wnet/newyork/ pbs.org] – [[New York: A Documentary Film]]</ref> | Over the weekend, the events were dramatized by the newspapers across the United States. On Monday, [[October 28]], more investors decided to get out of the market, and the slide continued with a record 13% loss in the Dow for the day. The next day, "Black Tuesday", [[October 29]] [[1929]], and 16.4 million shares were traded, a number that broke the record set five days earlier and that was not exceeded until [[1969]]. Author [[Richard Salsman|Richard M. Salsman]] wrote that on [[October 29]]—amid rumors that [[U.S. President]] [[Herbert Hoover]] would not veto the pending [[Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act|Smoot-Hawley Tariff]] bill—stock prices crashed even further."<ref name="salsman" /> [[William C. Durant]] joined with members of the [[Rockefeller family]] and other financial giants to buy large quantities of stocks in order to demonstrate to the public their confidence in the market, but their efforts failed to stop the slide. The DJIA lost another 12% that day. The ticker did not stop running until about 7:45 that evening. The market lost $14 billion in value that day, bringing the loss for the week to $30 billion, ten times more than the annual budget of the federal government, far more than the U.S. had spent in all of [[World War I]].<ref>[http://www.pbs.org/wnet/newyork/ pbs.org] – [[New York: A Documentary Film]]</ref> | ||

Revisão das 14h21min de 17 de outubro de 2007

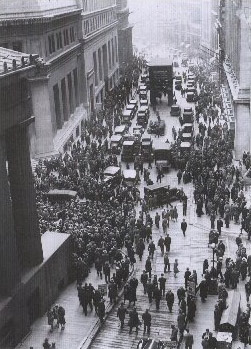

O Crash de 1929 foi um dos crashes bolsistas mais devastadores da história Americana. Ele consiste da Quinta-Feira negra (24 de Outubro de 1929), o crash inicial, e a Terça-Feira negra (29 de Outubro de 1929), o crash que semeou o pânico geral, 5 dias mais tarde. <ref>[1] "As cotações chegaram ao que aparenta ser um patamar permanentemente elevado. A euforia a os ganhos financeiros desse grande bull market foram estrelhaçados a 24 de Outubro de 1929, a Quinta-Feira negra, quando as cotações na NYSE colapsaram. As cotações cairam nesse dia e continuaram a cair, a uma velocidade sem precedentes, durante um mês inteiro."</ref>

Nos dias que precederam a Quinta-Feira negra o mercado estava instável. Períodos de venda em pânico e volumes elevados de transacções eram intervalados com breves períodos de subida de cotações e recuperação. Após o crash o Dow Jones recuperou no início de 1930, apenas para novamente cair, chegando ao fundo do grande bear market em 1932. O mercado não voltou aos seus níveis pre-1929 até ao final de 1954 <ref name="yahoo">DJIA 1929 to Present (Yahoo! Finance).</ref> e atingiu no seu ponto mais baixo, em 8 de Julho de 1932 , níveis que só tinham sido atingidos nos anos 1800s. <ref name="LiquidMarkets">Dow Jones 1900-2000</ref>

| “ | Quem tivesse comprado acções no meio de 1929 e as tivesse mantido, teria passado a maior parte da sua vida adulta antes de voltar ao breakeven. | ” |

Índice

Timeline

Após um supreendente bull market de 5 anos que viu o Dow Jones quintuplicar, as cotações atingiram o seu pico nos 381.17 em 3 de Setembro de 1929. Depois, o mercado caiu acentuadamente durante um mês, perdendo 17% do seu valor nesta primeira queda. As cotações encetaram aí uma recuperação de mais de metade das perdas em uma semana, apenas para voltarem a cair imediatamente após essa recuperação. A queda então acelerou para dentro da chamada "Quinta-Feira negra" (24 de Outubro de 1929). Um número recorde 12.9 milhões de acções foi transaccionado nesse dia.

À 1:00 da tarde de Sexta-feira, 25 de Outubro, alguns dos banqueiros líderes de Wall Street reuniram-se para procurar uma solução para o pânico e caos no trading floor. Esta reunião incluía Thomas W. Lamont, CEO do Morgan Bank; Albert Wiggin, CEO do Chase National Bank; e Charles E. Mitchell, presidente do National City Bank. Eles escolheram Richard Whitney, vice-presidente da bolsa, para os representar. Com os recursos financeiros dos banqueiros a suporta-lo, Whitney colocou um bid para comprar um grande bloco de acções da US Steel a um preço bem acima do preço presente do mercado. À medida que os traders surpreendidos olhavam, Whitney colocou depois bids similares em outras blue chips. Esta táctica era similar a uma táctica que foi usada para terminar o pânico de 1907, e teve sucesso em estancar a queda nesse dia. Neste caso, porém, o descanso seria apenas temporário.

Over the weekend, the events were dramatized by the newspapers across the United States. On Monday, October 28, more investors decided to get out of the market, and the slide continued with a record 13% loss in the Dow for the day. The next day, "Black Tuesday", October 29 1929, and 16.4 million shares were traded, a number that broke the record set five days earlier and that was not exceeded until 1969. Author Richard M. Salsman wrote that on October 29—amid rumors that U.S. President Herbert Hoover would not veto the pending Smoot-Hawley Tariff bill—stock prices crashed even further."<ref name="salsman" /> William C. Durant joined with members of the Rockefeller family and other financial giants to buy large quantities of stocks in order to demonstrate to the public their confidence in the market, but their efforts failed to stop the slide. The DJIA lost another 12% that day. The ticker did not stop running until about 7:45 that evening. The market lost $14 billion in value that day, bringing the loss for the week to $30 billion, ten times more than the annual budget of the federal government, far more than the U.S. had spent in all of World War I.<ref>pbs.org – New York: A Documentary Film</ref>

An interim bottom occurred on November 13, with the Dow closing at 198.6 that day. The market recovered for several months from that point, with the Dow reaching a secondary peak at 294.0 in April 1930. The market embarked on a steady slide in April 1931 that did not end until 1932 when the Dow closed at 41.22 on July 8, concluding a shattering 89% decline from the peak. This was the lowest the stock market had been since the 19th century.<ref name = "Liquid Markets">Liquid Markets.</ref>

Salsman observed that "As late as April 1942, U.S. stock prices were still 75% below their 1929 peak and would not revisit that level until November 1954—almost a quarter of a century later."<ref name="salsman" />

Economic fundamentals

Dow Jones Industrial, 1928-1930 The crash followed a speculative boom that had taken hold in the late 1920s, which had led millions of Americans to invest heavily in the stock market, a significant number even borrowing money to buy more stock. By August 1929, brokers were routinely lending small investors more than 2/3 of the face value of the stocks they were buying. Over $8.5 billion was out on loan, more than the entire amount of currency circulating in the U.S.<ref>pbs.org — New York: A Documentary Film</ref> The rising share prices encouraged more people to invest; people hoped the share prices would rise further. Speculation thus fueled further rises and created an economic bubble. The average P/E (price to earnings) ratio of S&P Composite stocks was 32.6 in September 1929 <ref> Shiller, Robert (2005-03-17). "Irrational Exuberance, Second Edition". Princeton University Press. Consultado a 2007-02-03.</ref>, clearly above historical norms.

On October 24, 1929 (with the Dow just past its September 3 peak of 381.17), the market finally turned down, and panic selling started. 12,894,650 shares were traded in a single day as people desperately tried to mitigate the situation. This mass sale was considered a major contributing factor to the Great Depression. Economists and historians, however, frequently differ in their views of the Crash's significance in this respect. Some hold that political over-reactions to the crash, such as the passage of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act through the U.S. Congress, caused more harm than the Crash itself.

Official investigation of the Crash

In 1931, the Pecora Commission was established by the U.S. Senate to study the causes of the Crash. The U.S. Congress passed the Glass-Steagall Act in 1933, which mandated a separation between commercial banks, which take deposits and extend loans, and investment banks, which underwrite, issue, and distribute stocks, bonds, and other securities.

After the experience of the 1929 crash, stock markets around the world instituted measures to temporarily suspend trading in the event of rapid declines, claiming that they would prevent such panic sales. The one-day crash of Monday, October 19, 1987, however, was even more severe than the Crash of 1929. On so-called Black Monday of 1987, the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell a full 22.6% (the markets quickly recovered, posting the largest one-day increase since 1932 only two days later).

Impact and academic debate

The Wall Street Crash had a major impact on the U.S. and world economy, and it has been the source of intense academic debate—historical, economic and political—from its aftermath until the present day. The crash marked the beginning of widespread and long-lasting consequences for the United States. The main question is: Did the crash cause the depression, or did it merely coincide with the bursting of a credit-inspired economic bubble? The decline in stock prices caused bankruptcies and severe macroeconomic difficulties including business closures, firing of workers and other economic repression measures. The resultant rise of mass unemployment and the depression is seen as a direct result of the crash, though it is by no means the sole event that contributed to the depression; it is usually seen as having the greatest impact on the events that followed. Therefore the Wall Street Crash is widely regarded as signaling the downward economic slide that initiated the Great Depression.

Many academics see the Wall Street Crash of 1929 as part of an historical process that was a part of the new theories of Boom and bust. According to economists such as Joseph Schumpeter and Nikolai Kondratieff the crash was merely a historical event in the continuing process known as Economic cycles. The impact of the crash was merely to increase the speed at which the cycle proceeded to its next level. According to the economist Milton Friedman, in the immediate aftermath of the crash, the Federal Reserve did not sufficiently expand the money supply and so turned the recession into a depression.

Ver também

Referências

Bibliografia

- Brooks, John. (1969). Once in Golconda. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-393-01375-8.

- Galbraith, John Kenneth. (1955). The Great Crash: 1929. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-85999-9.

- Klingaman, William K. (1989). 1929: The Year of the Great Crash. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-060-16081-0.

- Salsman, Richard M. “The Cause and Consequences of the Great Depression” in The Intellectual Activist, ISSN 0730-2355.

- “Part 1: What Made the Roaring ’20s Roar”, June, 2004, pp. 16–24.

- “Part 2: Hoover’s Progressive Assault on Business”, July, 2004, pp. 10–20.

- “Part 3: Roosevelt's Raw Deal”, August, 2004, pp. 9–20.

- “Part 4: Freedom and Prosperity”, January, 2005, pp. 14–23.

- Shachtman, Tom. (1979). The Day America Crashed. New York: G.P. Putnam. ISBN 0-399-11613-3.